Shri Jagannath Temple and the Evolution of Religious Traditions in Odisha( part-2)

By Lokanath Mishra

Puranic Perspective : Temple in Satya Yuga

The origins of the Jagannath temple are described in various Puranas and epics, which offer a sacred narrative distinct from the historian’s view.

According to the Skanda Purana, in Satya Yuga, King Indradyumna of the Somavamsa dynasty from Avanti built the temple of Lord Jagannath at Puri. He invited Lord Brahma, the creator, to perform the Pratistha (installation) of the deities. During King Indradyumna’s journey to Brahmaloka, a ruler named Gala Madhav worshipped Madhav in the same temple.

The antiquity of Jagannath worship is also confirmed in literary references. In the Mahabharata (Vana Parva) and in the Srimad Bhagavad Gita (Purushottama Yoga), the name of Lord Jagannath is explicitly mentioned. These Puranic and epic accounts establish that the Jagannath temple is not only ancient but also deeply connected with India’s mythological and religious traditions.

Thus, from the Puranic viewpoint, the Jagannath temple was established in Satya Yuga and has been renewed many times across the four Yugas by different dynasties.

Historical Reconstructions of the Jagannath Temple

The historical accounts, drawn from inscriptions and chronicles, present a sequence of reconstructions over centuries:

• 10th Century (949–959 A.D.): King Jajati Keshari of the Somavamsi dynasty rebuilt the temple on the advice of Adi Shankaracharya. He brought the Trinity (Jagannath, Balabhadra, and Subhadra) from Subarnapur back to Puri and installed them in the newly built temple.

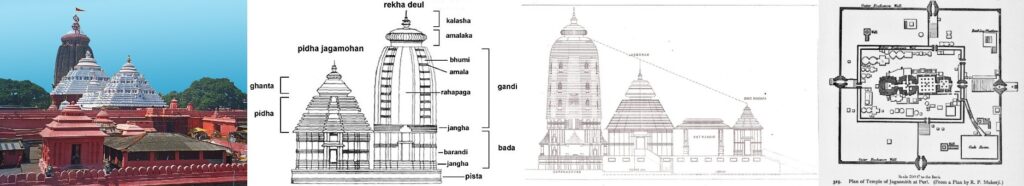

• 12th Century (1134 A.D.): King Ananta Varman Chodaganga Deva of the Eastern Ganga dynasty began the construction of the present grand temple structure.

• 12th Century (1190–1198 A.D.): King Anangabhima Deva, successor to Chodaganga Deva, completed the work, giving the temple its present form.

From a historical perspective, therefore, the temple as seen today was first renewed in the 10th century, enlarged in the 11th, and fully completed in the 12th century. The current temple is thus around 800 years old.

Migration and Role of Kannauj Brahmins

For the successful functioning of temple rituals and ceremonies, kings of Odisha brought Brahmins from Kannauj in two significant phases:

1. 10th Century Migration: During Yayati Keshari’s reign, Kannauj Brahmins were invited for the Ashvamedha sacrifice and to strengthen the Vedic and ritualistic framework of the Jagannath cult.

2. 12th Century Migration (1151–1152 A.D.): A large-scale settlement of about 6,000 Kannauj Brahmins took place around Puri during the time of temple reconstruction under the Ganga dynasty.

These Brahmins were settled in Brahmin Sasan villages, where they were allotted land, houses, and resources. They were entrusted with a range of responsibilities:

• Performing karma-kanda rituals—marriages, thread ceremonies, house consecrations, funeral rites, homas, havans, and temple services.

• Training the Sevayats (temple servants) in ritual practices.

• Advising the king on religious and spiritual matters.

• Teaching society about dharma, karma, yoga, prayer, and meditation.

Thus, they not only ensured the continuity of temple rituals but also functioned as teachers and guides for society at large.

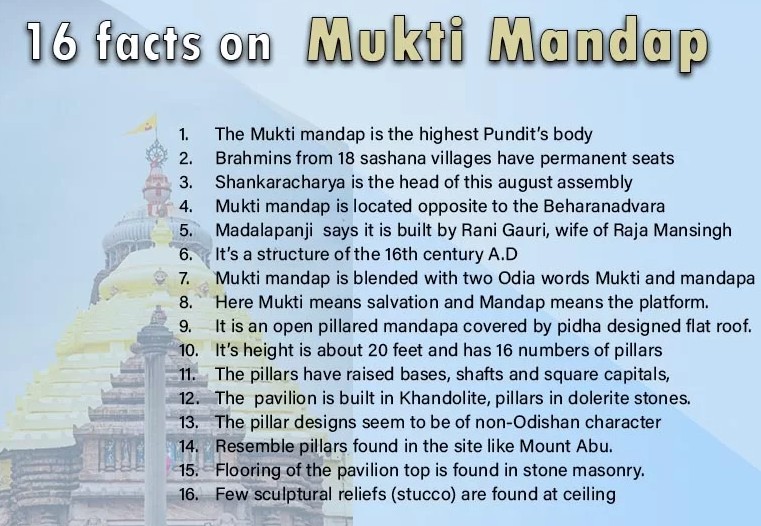

Mukti Mandapa : Council of Learned Brahmins

One of the most significant institutions associated with the Jagannath temple is the Mukti Mandapa, a platform of salvation situated inside the temple complex, near the Adi Nrusingha temple on the southern side.

Origins and Structure

According to the Madala Panji, Mukti Mandapa was constructed in the 15th century at the request of Queen Gauri Mahadevi, consort of King Man Singh of Jaipur, the commander-in-chief under the Mughal Emperor Akbar.

The platform is built of black granite stone, raised five feet above the ground, covering an area of about 900 square feet. It is square in shape, open on all sides, and supported by sixteen stone pillars beneath a roof 13 feet high. Each pillar stands about eight feet tall. Stone idols of various deities—including Lord Nrusingha, Lord Ganesh, Goddess Durga, Goddess Kali, Lord Brahma, and Lord Krishna—are placed around the platform. Symbolically, the sixteen pillars are believed to represent the Shohala Sasan (16 Brahmin settlements) around Puri established by Ramachandra Deva of the Bhoi dynasty. Later, eight more villages were added, bringing the number to 24.

Functions and Importance

The Mukti Mandapa serves as a council of Brahmin scholars, akin to a religious judiciary. Its functions include:

• Acting as the final authority in disputes related to rituals, worship, and religious practices.

• Guiding kings and devotees on spiritual, ritualistic, and social issues.

• Blessing pilgrims and devotees who seek advice and salvation through prescribed rites.

• Serving as a forum for learned discussions under the permanent presidency of the Shankaracharya of Govardhan Matha, Puri.

Devotees often bow at the feet of the Pandits seated on the Mukti Mandapa, seeking blessings and counsel for their personal and social lives.

Integration of Traditions

The settlement of Kannauj Brahmins, the institution of Mukti Mandapa, and the inclusiveness initiated by Shankaracharya all converged to make the Jagannath temple not just a Vaishnava shrine but a unique confluence of Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism, Buddhism, Jainism, and tribal faiths. In Brahmin Sasan villages, the Brahmins themselves worshipped Krishna, Shiva, and Durga collectively, reinforcing the unity of traditions.

Mukti Mandapa and the Evolution of the Pandit Sabha

Before the Mukti Mandapa took its present form in the 15th century, there already existed an assembly of learned Brahmins at Puri. This Pandit Sabha played a vital role in interpreting religious law, guiding temple rituals, and advising both kings and devotees.

• First Gathering at the South Gate: After the large-scale migration of Kannauj Brahmins in the 12th century, the Pandit Sabha initially assembled at the South Gate of the Jagannath temple. Here, the scholars gathered regularly to deliberate on ritual matters and pass collective judgments on religious issues.

• Shift Near the Bimala Temple: Following the advice of Adi Shankaracharya, the Pandit Sabha later moved to the left side of the Bimala Temple inside the complex. This spot, where the present temple library is located, became their meeting place for several centuries. The move was significant because the Goddess Bimala represents Shakti, and all temple offerings to Lord Jagannath are considered complete only after being first offered to Bimala Devi. Holding deliberations here symbolized the Sabha’s authority as rooted in the unifying principle of Shakti and Dharma.

The Formal Mukti Mandapa

The Madala Panji records that in the 15th century, at the request of Queen Gauri Mahadevi (consort of Man Singh of Jaipur), the permanent Mukti Mandapa was constructed. This granite platform institutionalized the Pandit Sabha in stone and form, providing a designated sacred seat of authority. The Mukti Mandapa is square-shape, five feet high, supported by sixteen pillars, and open on all four sides.

• The Mukti Mandapa became the final religious judiciary for disputes concerning worship, ritual practices, and societal dharma.

• The Shankaracharya of Govardhan Matha is its permanent head, presiding over deliberations.

• In earlier times, disputes were first referred to the king of Puri, who would call upon the Pandits of the Mukti Mandapa for the final verdict.

• Devotees still approach the Mukti Mandapa to seek blessings, counseling, and guidance on spiritual and personal matters.

Thus, the Mukti Mandapa represents the institutional continuity of the Pandit Sabha, evolving from its early gatherings at the South Gate and near the Bimala Temple into a permanent council of spiritual authority.

Conclusion

The Jagannath temple of Puri, whether viewed through the Puranic lens of Satya Yuga or the historian’s account of reconstructions across centuries, stands as the world’s oldest living temple tradition. Its rituals, institutions, and philosophical inclusiveness embody Odisha’s identity as a sacred land of religious synthesis. From King Indradyumna and Jajati Keshari to Ananta Varman Chodaganga Deva and Anangabhima Deva, from Kannauj Brahmins to the Mukti Mandapa Pandits, every layer of its history reflects continuity, adaptation, and resilience.

( to be continued)

Shri Jagannath Temple and the Evolution of Religious Traditions in Odisha ( part-1)

A Story of Dvapar Yuga in Prose: ( Part- 11 B)

A Story of Dvapar Yuga in Prose (Part- 11 A )

Pingback: Shri Jagannath Temple and the evolution of religious traditions in Odisha : ( part-3) - UniverseHeaven

“Heartfelt thanks to the author for this insightful and well-researched article. Your work beautifully sheds light on Odisha’s rich religious heritage and the timeless traditions of the Jagannath Temple. Grateful for your dedication and valuable contribution to literature and history.”