Shri Jagannath Temple and the evolution of religious traditions in Odisha: ( part-3)

By Lokanath Mishra

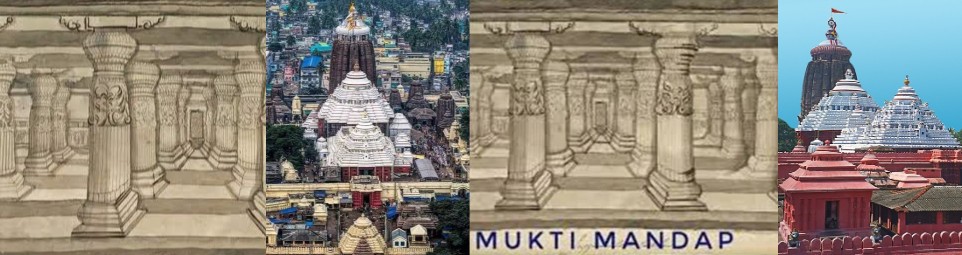

Mukti Mandapa of Jagannath Temple: The Council of Salvation

The Jagannath Temple of Puri, one of the holiest shrines in Hinduism, is not only a center of devotion but also of culture, tradition, and scholarship. Within its sacred precincts lies the Mukti Mandapa, a high granite platform of immense religious and historical significance. The very name combines two Odia words—Mukti (salvation) and Mandapa (platform)—meaning the “Platform of Salvation.” True to its name, it has served as a spiritual court, a center of learning, and a final authority in matters of religion and rituals for centuries.

Historical Origins

The Madala Panji, the temple chronicle, records that the present Mukti Mandapa was constructed in the 15th century at the request of Queen Gauri Mahadevi, consort of Raja Man Singh of Jaipur, the Mughal general under Emperor Akbar. The story of its creation is intertwined with the political history of Odisha.

When Akbar’s forces attempted to conquer Khurda, ruled then by King Ramachandra Deva I, the valiant Paikas (warriors) repulsed them thrice. Realizing the futility of conquest, Man Singh recognized Ramachandra Deva as the legitimate ruler of Odisha, granting him full authority over the Jagannath Temple.

During his pilgrimage to Puri in the nineteenth year of Ramachandra Deva’s reign, Man Singh’s queen observed that the old Mukti Mandapa, then located near the southern gate (Dakshina Dwara) was in ruins and the Brahmins were sitting near to Maa Bimala Temple. She financed the construction of the new platform, also called Brahmasana, with sixteen pillars—each symbolically linked to the shohola shasana (sixteen Brahmin settlements around Puri). Over time, the number of represented sasanas grew to 24, reflecting the temple’s expanding intellectual and ritual community.

Architectural Features

The Mukti Mandapa is a striking structure of black granite, elevated about five feet above the ground and covering 900 square feet in a square form. Its flat roof, set thirteen feet high, is supported by sixteen elegant stone pillars—twelve around the periphery and four at the center. Each pillar stands about eight feet tall.

Carvings of deities such as Lord Narasimha, Lord Ganesha, Goddess Durga, Goddess Kali, Lord Brahma, and Lord Krishna adorn the platform, emphasizing its sanctity. The open design allows accessibility from all sides, underscoring its function as a public and inclusive space for spiritual discourse.

Seat of Knowledge and Learning

Even before its reconstruction in the 16th century, the Mukti Mandapa was revered as the axis of Odia culture and intellectual life. Eminent scholars tested their scholarship here. Literary luminaries such as Murari Misra (author of Anargha Raghava) and Krishna Misra (author of Prabodha Chandrodoya) demonstrated their mastery in this very assembly.

The tradition continued with later scholars like Balabhadra Rajaguru and Purandara Purohita during the reign of Prataparudra Deva, and poets like Devadurlabha Dasa, who made references to the Mukti Mandapa in their works. The Panchasakha poets ( both old and modern groups) central to Odia literature and spiritual reform, were deeply connected to the intellectual traditions fostered by this sacred platform. Atibadi Jagannath Dash was born in the village Kapileswar Pur, Gopabandhu Dash, Nilakantha Dash, Godabarish Mishra, Acharya Hari Har, Pandita Kurpasindhu Mishra etc, the modern renowned odiya poets and freedom fighters were born in the Brahmin Shasan villages near to the Shri Jagannath Temple, Puri. This Brahmin Shasan villages were played a crucial role in freedom movement.

Judicial and Religious Authority

The Mukti Mandapa has long functioned as the supreme council of Brahmin scholars (Pandit Sabha) in Puri. Presided over permanently by the Shankaracharya of Puri’s Govardhan Matha, it serves as the final judiciary in matters of ritual practice, temple administration, and religious disputes.

In earlier centuries, disputes concerning worship were referred first to the Raja of Puri, who would summon the Pandits of the Mukti Mandapa for the ultimate verdict. This tradition continues today: issues related to temple rites, almanac (Panji) approval, and religious penances (prayaschitta) are resolved here. Notably, when the iconoclastic general Kalapahada sought reconversion to Hinduism, it was the Mukti Mandapa that denied his request—an example of its decisive spiritual authority.

This judicial role demonstrates the democratic ethos of Jagannath culture, where even the Puja Panda Niyoga , other sevayat niyoga and temple administrators defer to the learned assembly for final decisions.

Rituals and Daily Practices

The Mukti Mandapa is deeply integrated into the temple’s religious life. During the Navakalevara festival, when the wooden images of the deities are replaced, the Mukti Mandapa Pandits perform the Pratistha Homa (consecration ritual) for the new idols.

Every day, the Puranas and Veda are recited here, with their meanings explained to pilgrims. Two thalis of Mahaprasad (sacred food) are sent daily after the morning and midday worship, distributed among the Brahmins seated on the platform. Another special offering, the Mahadei Thali, endowed by the Queen of Athagada, is also distributed after first being offered to Goddess Kali near the Mandapa.

Spiritual Significance

For devotees, the Mukti Mandapa is more than a platform of scholarship or authority—it is a pathway to liberation. Pilgrims often bow before the Brahmins seated there, seeking blessings and guidance for both personal and social challenges. The belief endures that following the rituals and prescriptions of the Mukti Mandapa Pandits frees one from sins and ensures salvation.

Thus, the Mukti Mandapa is not only a physical structure but also a living institution—uniting spirituality, culture, scholarship, and justice within the heart of Jagannath’s temple.

Conclusion

The Mukti Mandapa of Puri embodies the timeless union of faith and reason in Jagannath culture. It has been a witness to political negotiations, a stage for literary brilliance, a court of ultimate justice, and a sanctuary of divine grace. Standing firm on its granite pillars, it continues to uphold traditions while guiding countless devotees on the path of salvation—true to its name, the Platform of Liberation.

( to be continued)

Shri Jagannath Temple and the Evolution of Religious Traditions in Odisha( part-2)

Shri Jagannath Temple and the Evolution of Religious Traditions in Odisha ( part-1)

The Divine Journey of Lokanath Mishra

Pingback: Shri Jagannath Temple and the Evolution of Religious Traditions in Odisha ( part-4) - UniverseHeaven