A Story of Dvapar Yuga in Prose ( part-27-C)

By Lokanath Mishra

( Mahabharata in Prose)

Yudhishthira, in a certain manner, compelled the guards to return to Hastinapura. After returning, the chief guard met Shakuni and informed him, “One horseman had earlier gone from Hastinapura to Varanavata. Who he was and why he went there could not be ascertained. But immediately thereafter, Prince Yudhishthira ordered us to return.”

A mysterious smile appeared on Shakuni’s face and then faded. His suspicion that “Vidura will not remain quietly seated” proved to be true. He dismissed the guards and began discussions with Duryodhana. The main question now was—who would set fire to the House of Lac?

When Purochana was summoned and asked to stay at Varanavata, he replied, “While poisoned food was being served earlier, Bhima had glanced at me once or twice. Though most of the time his attention was on the food, if he suspects me even slightly, my wife will become a widow prematurely.”

Shakuni replied, “O Brahmin, even if you do not obey our command, the chances of your wife remaining a married woman are very slim. There is a skilled actor in the city troupe. Through disguise, he will alter your appearance. I shall send him to you. From today, your name shall be Vailochana. Prepare yourself. It is our responsibility to inform King Dhritarashtra and obtain his approval. You shall go there and say that the king has sent you to cook.”

Disguised, Purochana reached Varanavata and introduced himself as a cook named Vailochana. Claiming that King Dhritarashtra had sent him, he produced a royal letter. Mother Kunti was worried about Bhima, who had grown weary of subsisting only on fruits and roots. She wished to retain Vailochana, but remembering Vidura’s cautious words, she remained silent.

Yudhishthira said, “We were born and raised in the forests near Mount Shatashringa. Living on fruits and roots is our habit. There is no need for cooking. If you wish, you may stay and partake of fruits with us.”

Purochana returned.

Vidura understood that it was crucial to know where the mouth of the tunnel would open. The following night, he went with a miner to the newly built palace at Varanavata. There were no guards and no security arrangements—only a single lock hung at the gate. Vidura was inwardly disturbed by the Pandavas’ apparent lack of caution.

He signaled the miner to dig near the wall. As soon as the miner approached, a voice shouted, “Stop right there!” Bhima, sitting atop the wall with his mace, had been watching them. He leapt down, recognized Uncle Vidura, and bowed respectfully, saying, “You gave no signal. I was about to cause an unfortunate incident. Who is this?”

Satisfied with the vigilance, Vidura said, “First take us inside. Open the lock.”

Inside, Vidura discussed his future plan. Bhima was entrusted with arranging food for the miner. It was decided in which room the tunnel would open and how it would lead to the river Ganga. Vidura instructed that the tunnel be wide and tall enough for Bhima to pass through freely. The miner assured him that the work would be completed swiftly.

Walking along the riverbank, Vidura noticed a boatman sitting in a boat floating on the river. He called him over and asked why he was there at such a late hour. The boatman replied that he ferried people across the river day and night.

Vidura offered him far greater wealth than his usual earnings, on the condition that he follow instructions. The boatman hesitated, citing royal appointment, but Vidura revealed his identity and assured protection. He instructed the boatman to bring his boat near the tunnel’s exit, submerge it there, stay home during the day, and guard the place at night. On one night, the five brothers along with their mother would emerge from the tunnel, and the boatman was to ferry them across. Vidura gave him a signet ring and warned him to keep the plan secret.

Meanwhile, Purochana returned to Shakuni and Duryodhana and reported his failure. There was no access to fire, and he was not allowed to cook. Another plan was devised. Duryodhana and Shakuni sought King Dhritarashtra’s approval to establish blacksmith workshops nearby, claiming it would reduce the Pandavas’ isolation and aid settlement. Dhritarashtra agreed.

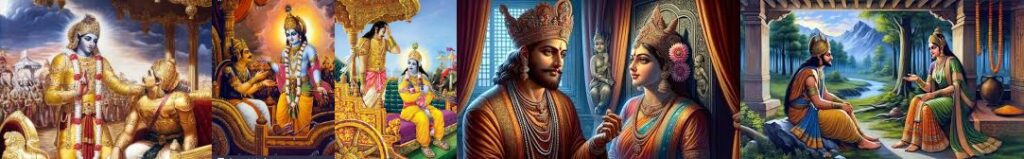

Shakuni personally escorted Purochana and ironworkers to Varanavata and set up blacksmith shops near the palace. Seeing the commotion, Yudhishthira arrived and questioned Shakuni. With feigned affection, Shakuni explained that the king was concerned for their welfare and had ordered the establishment of habitation and workshops. He also asked that the Brahmin remain with them to help.

Yudhishthira expressed gratitude and invited Shakuni to stay at the palace, but Shakuni declined and left Purochana behind in a servant’s quarters. Someone, however, kept a watchful eye on him.

Back in Hastinapura, Shakuni boasted to Duryodhana that the throne was now secure. Their laughter echoed—until Karna entered. Sensing secrecy, Karna questioned why he had not been told the full truth. Shakuni deflected, citing Karna’s attachment to dharma, and claimed all actions were for Duryodhana’s good. Karna remained unconvinced and left dissatisfied.

The blacksmiths were, in truth, Purochana’s accomplices, maintaining constant access to fire. Purochana awaited Shakuni’s signal. Instructions arrived—on the coming new moon night, the palace was to be set ablaze.

Unbeknownst to them, someone overheard the discussion and vanished into the darkness.

Vidura, upon hearing the spy’s report, grew anxious. If the tunnel was not complete, how would they escape? Late at night, the miner reassured him that the tunnel was ready and opened into the eldest prince’s chamber.

Vidura folded his hands and prayed to Lord Krishna:

“O Krishna, O Compassionate One, the Pandavas have always been under Your protection. Now their safety rests with You. Protect them from all dangers.”

“The House of Lac – A Conspiracy of Fire and Faith”**

The episode of the Jatugriha (House of Lac) in the Mahābhārata is not merely a tale of attempted murder—it is a profound study of political deceit, moral vigilance, and divine guardianship.

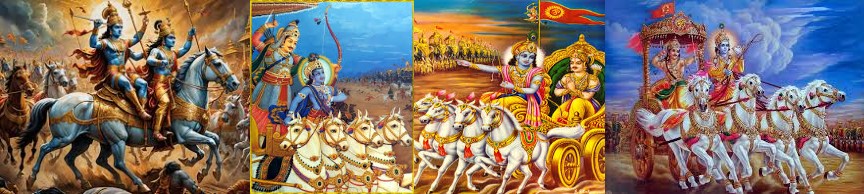

At one level, this narrative exposes the chilling precision with which Shakuni and Duryodhana plotted the annihilation of the Pandavas. Fire, the most sacred purifier in Vedic culture, is here turned into a weapon of treachery. The irony is stark: blacksmith workshops, symbols of creation and industry, are transformed into sources of destruction.

Yet, standing against this darkness is Vidura, the embodiment of wisdom and quiet resistance. Unlike Bhima’s strength or Arjuna’s valor, Vidura’s weapon is foresight. He does not confront evil openly; he outmaneuvers it. His use of miners, spies, and even a humble boatman reveals a sophisticated intelligence network—arguably one of the earliest depictions of strategic counter-espionage in epic literature.

Equally significant is Yudhishthira’s restraint. Though aware of danger, he adheres to courtesy and dharma, never openly accusing his elders. This moral discipline becomes both his strength and his vulnerability. Bhima, by contrast, represents alert physical vigilance—watching from the ramparts, mace in hand, ready to act at the slightest provocation.

The figure of Karna adds further complexity. Though aligned with Duryodhana, his discomfort hints that destiny has already begun to distance him from the unfolding conspiracy. Karna’s moral confusion underscores one of the epic’s recurring themes: loyalty without ethical clarity leads to inner unrest.

Above all looms the unseen presence of Krishna. Though physically absent, He is spiritually invoked, reminding the reader that while human intelligence may plan escape, ultimate protection flows from divine will. The tunnel leading to the Ganga is symbolic—a passage from death to life, from confinement to freedom, from human malice to cosmic justice.

Thus, the House of Lac is not just a burning palace—it is a crucible in which destinies are tested, alliances revealed, and the eternal struggle between adharma and dharma takes a decisive turn.

Fire was meant to erase the Pandavas.

Instead, it illuminated the path of their survival.

(To be continued)